LEVANT PEACE PROJECT

peace@levantpeace.org

-- A Second Treaty of Lausanne --

In the aftermath of World War I, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire reshaped the Middle East, as European powers imposed new political boundaries through the mandates of the League of Nations. The French mandate encompassed the northern Levant—comprising present-day Syria, Lebanon, and parts of southeastern Turkey—while the British mandate governed the southern Levant, including Palestine, Jordan, and Egypt. These artificial borders disrupted centuries-old social, ethnic, and religious continuities, laying the foundation for enduring instability.

The Republic of Turkey emerged from the Ottoman collapse with sweeping reforms under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, including a dramatic cultural and linguistic transformation. Amid the population upheavals that followed, the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece provided a blueprint for peaceful demographic realignment: over 1.5 million people were voluntarily resettled to establish more cohesive, harmonious national communities. This model of negotiated population transfer—though difficult—successfully resolved intercommunal tensions in a post-imperial context.

The region of historic Palestine (Eretz Yisrael) underwent its own demographic transformation during this period. Waves of Jewish return, land purchases, and Ottoman-era population movements—particularly from the northern Levant after the Napoleonic campaigns—led to a complex and often contentious coexistence. Under British administration, many Muslim communities became "protected subjects," further entrenching divisions. Today, unresolved questions of identity, citizenship, and belonging continue to fuel conflict and suffering, especially for displaced Palestinian populations.

Currently, the Gaza population—many of whom have no familial or ancestral ties to Gaza prior to 1918—remain trapped in a devastated, overcrowded enclave, cut off from meaningful statehood, economic opportunity, or regional mobility. These populations are the descendants of refugees from various parts of the former Ottoman Empire, primarily from the northern Levant. As such, their connection to Gaza is largely circumstantial, a result of political partitions imposed by colonial mandates and international conflicts.

Beyond Gaza, there are millions of disenfranchised Palestinian refugees across the Middle East. In Jordan, over 2 million registered refugees live under varying legal statuses, with many denied full citizenship. In Lebanon, approximately 475,000 are registered with UNRWA, though fewer than half remain in the country; most live in legal limbo, barred from owning property, accessing healthcare, or holding certain jobs. In Syria, over 450,000 were registered prior to the civil war, with most displaced again, some multiple times, within or beyond Syria's borders. Egypt hosts tens of thousands of unrecognized Palestinian refugees without formal legal status or access to public services. In Iraq, the remaining Palestinian population—once over 30,000—has dwindled to a few thousand, facing harassment and statelessness. Turkey is home to thousands more, many of whom fled the Syrian conflict and remain in legal uncertainty.

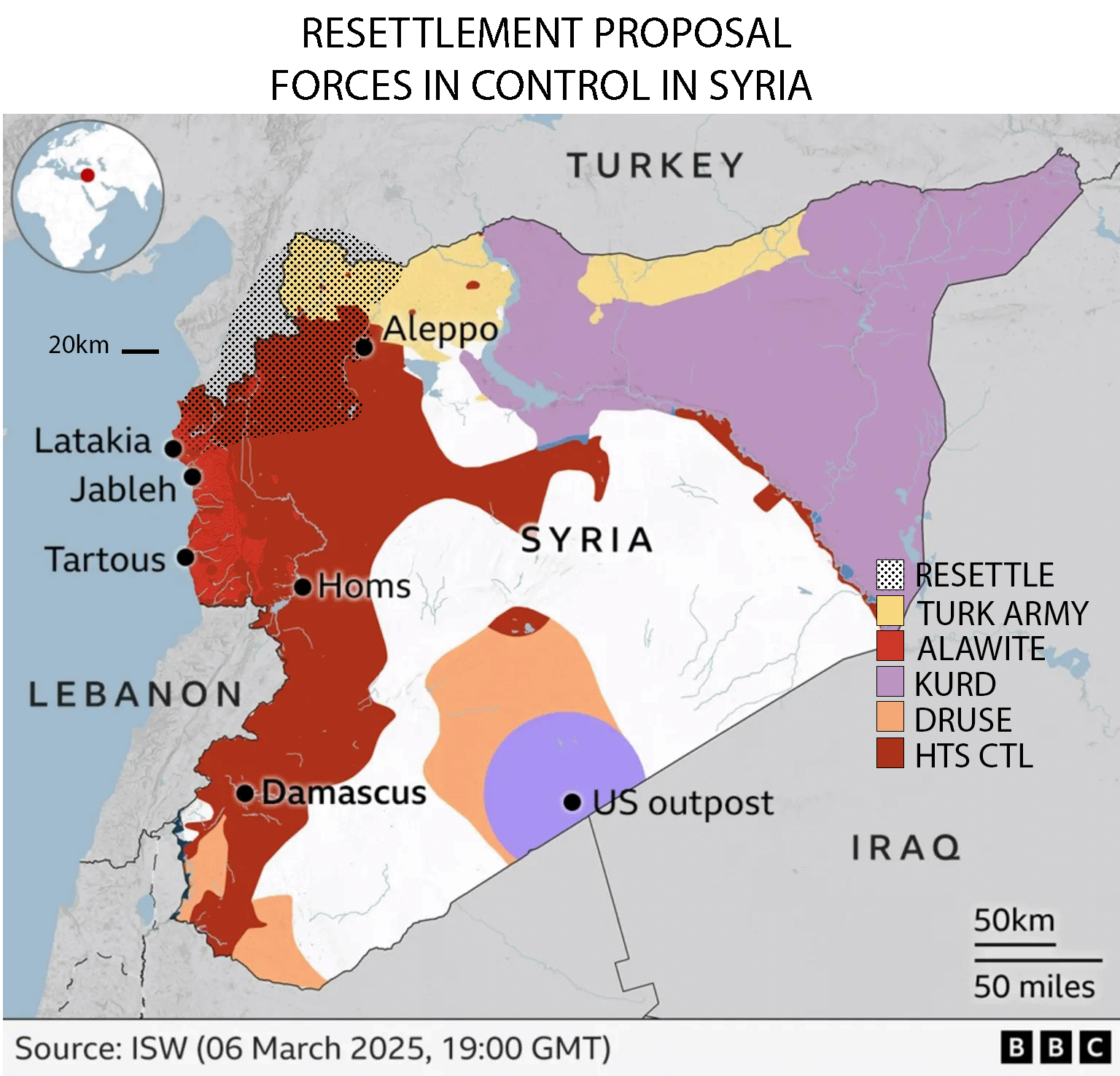

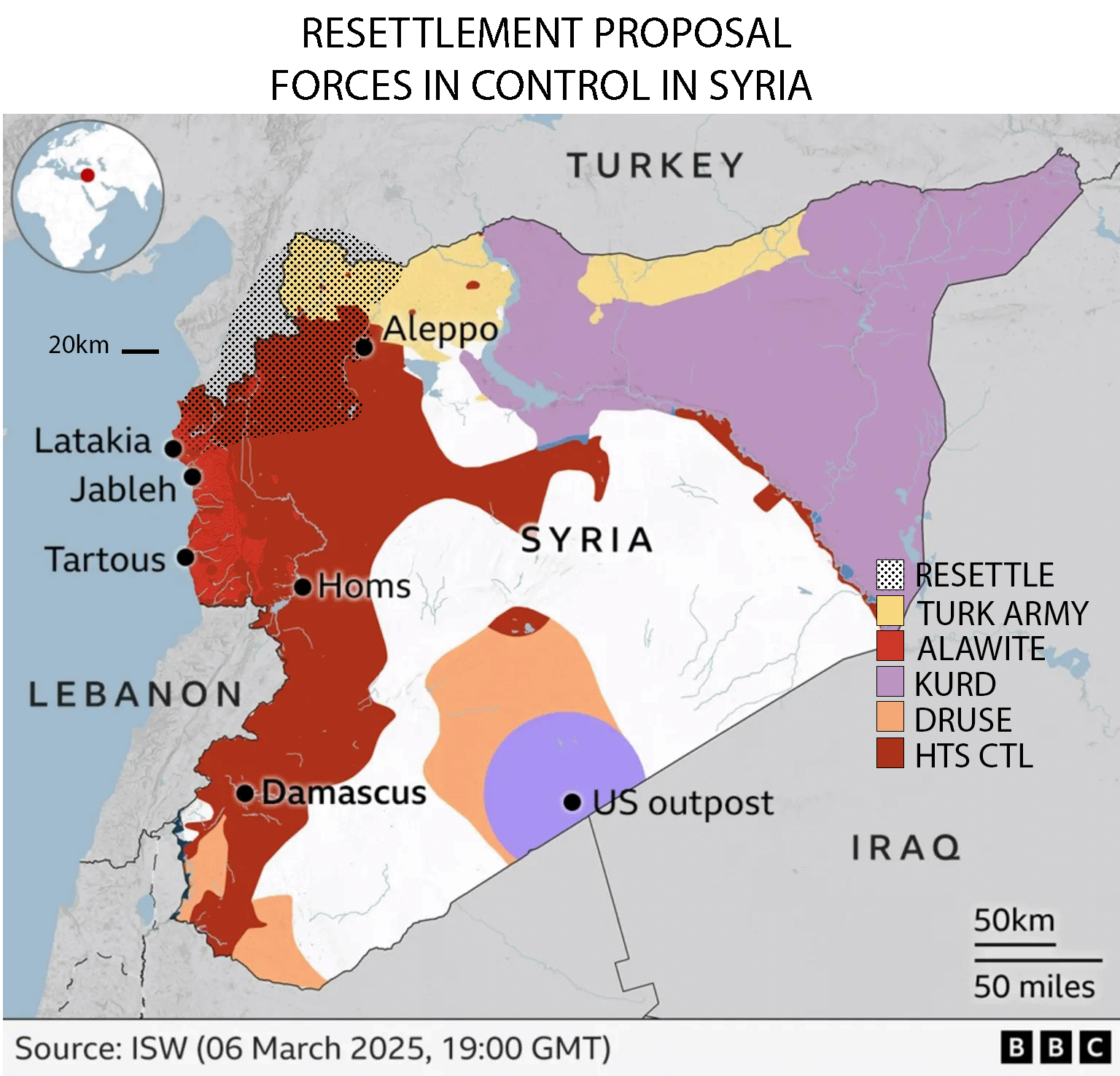

This vast, disenfranchised diaspora exists without a state, without citizenship, and without the protection of international law. The resettlement of the Gaza population—many of whom are originally from regions within modern-day Syria—could serve as the first step in a broader, voluntary, and internationally supported effort to establish a Syro-Palestinian homeland in northwestern Syria. Such a move would lay the groundwork for resolving the broader crisis of statelessness among Palestinians across the region, in a manner consistent with historical precedents and regional stability.

We therefore propose the establishment of a Syro-Palestinian Nation-State in northwestern Syria, built upon a modern, humanitarian reinterpretation of the Treaty of Lausanne. This Second Lausanne Accord would provide a legal and political foundation for the voluntary repatriation and integration of Palestinian and Gazan refugees as former Ottoman subjects. It calls for international recognition of their historical ties to the region, and advocates for their enfranchisement—either through Turkish citizenship or through a new federal entity in Syria under Turkish administration.

This initiative is not merely a historical redress but a forward-looking path to regional stability. It seeks to harmonize demographic realities with national aspirations, just as postwar treaties have done elsewhere in Europe. By aligning with precedents of successful population resolutions, this proposal offers a bold but peaceful roadmap for resolving one of the Middle East's most intractable humanitarian crises.

Legal Recognition of Ottoman Citizenship: Turkey acknowledges Gazans of Ottoman descent under the Tanzimat reforms (1800s) as eligible for citizenship or special residency status. Similar to Israel’s Law of Return, Gazans would be entitled to relocate to Turkey or Turkish-administered areas in Syria.

WE NEED YOUR HELP, CONTACT YOUR POLITICIANS & LEADERSHIP

ON YOUR REQUEST WE WILL SEND OUR WHITE PAPER

& PROPOSAL

CONTACT US AT: PEACE@LEVANTPEACE.ORG

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS (Under construction, please make suggestions) |

Jewish History (<586 BCE -): From the destruction of the First Temple (586 BCE) and the exile of the Jews by the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzer, the populations of the Levant from Gaza to Turkey have endured an ending series of wars, expulsions, exterminations, and restorations. The Babylonians were conquered by the Persians who under Daris II restored the Jewish population and built the Second Temple about the Foundation Stone. Then came the Greeks and the Romans. In 70 CE, the Roman Emporer Titus destroyed of the Second Temple (70 CE), and exiled and enslaved of the Jews. Christian History (33 CE -): Tradition has See of Rome as being founded by Apostles Peter and Paul in the 1st century. Nearly 2000 years later, the Vatican (Tomb of St. Peter 64 CE) and the Arch of Titus (81 CE) in its famous relief the plunder of the Temple artifacts attest to their impact. As pagan Rome declined, the Byzantine Christian Empire arose with Constantinople (381 CE) and the Hagia Sophia (581 CE) as its sacred church. center. In Jerusalem, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (335 CE) was consecrated by Constantine I. Early Muslim History (610 CE -1096 CE): The Levant was a culturally and religiously diverse region under early Islamic rule which included a Muslim majority alongside significant communities of Eastern Christians—such as Greek Orthodox, Syriac, Maronite, and Armenian Christians—and Jews, particularly in cities like Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Sidon. These groups coexisted for centuries under Islamic governance, living under the subordinate status of dhimmi. Crusades (1096-1291): The Crusades, beginning with the First Crusade (1096–1099), drastically disrupted the Levant’s demographic balance. When Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, they massacred large numbers of Muslims and Jews, effectively depopulating the city’s non-Christian inhabitants. Western Europeans—referred to as Franks—established the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states, forming a ruling elite often isolated from the local population. Although some intermarriage and cultural exchange occurred, the Franks generally remained separate from indigenous communities. Eastern Christians were caught in the middle—sometimes mistrusted by both sides—and often shifted allegiances between Crusaders and Muslim powers such as the Ayyubid Sultanate, founded by Saladin, who recaptured Jerusalem in 1187 and invited Muslims, Jews, and Eastern Christians to repopulate the city. Post-Crusades (1291-1516): After the fall of the last Crusader stronghold at Acre in 1291, European influence in the Levant sharply declined. Muslim powers such as the Mamluk Sultanate, and later the Ottoman Empire (beginning in 1516), restored Islamic dominance, and many cities were resettled with Muslims from surrounding regions. Some Christian groups, such as the Maronites in Lebanon, maintained autonomy under Ottoman rule, while Jewish communities slowly reestablished themselves in cities like Safed and Jerusalem Ottoman Empire(1516-1917) The Levant during the Ottoman Empire—The region that includes modern-day Eretz Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan—underwent significant political, social, and economic transformations between the 16th and early 20th centuries. One particularly important development, especially from the late 19th century onward, was the opening of land ownership to Jews and the purchase of land in the context of Zionist immigration and settlement. Ottoman Rule in the Levant (1516–1917)The Levant became part of the Ottoman Empire after the defeat of the Mamluks in 1516. It remained under Ottoman control until the end of World War I, when the empire collapsed and the region came under British and French mandates. The population was religiously and ethnically diverse, including Muslims (Sunni and Shia), Christians (Eastern Orthodox, Maronite, Armenian, and others), Jews, and Druze. The Levant was divided into Vilayet (provinces) of Beirut (Wilāyat Bayrūt) which included Haifa, Acre (Akko), Nazareth, Safed (Tzfat), Galilee. It was split off from the larger Vilayet of Syria in 1888; the. Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem (Sanjak of Jerusalem) was directly governed from Istanbul including Bethlehem and Hebron; and the Vilayet of Damascus (Wilāyat Dimashq) which included parts of southern Eretz Yisrael The Ottoman Land Code of 1858 required registration of land ownership, which shifted land from communal or tribal forms into private, legally recognized holdings. This reform led to concentration of land ownership among urban elites or absentee landlords, since many peasants refused to register land in their names due to tax burdens or fear of conscription. Mark Twain visited Eretz Yisrael in 1867 observing that "Jerusalem is mournful, and dreary, and lifeless. I would not desire to live here. He found Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee “desolate” and far removed from the biblical romance many Westerners imagined, and Nazareth was described as a sleepy village. Eretz Yisrael was “A desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds—a silent mournful expanse... A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action.” The change in the Land Code (1858) enabled Jewish land acquisition accelerated by the rising European Zionist movement and persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire. Joining the indigenous Jewish community, in 1882 Jews from Eastern Europe began the First Aliyah, settling primarily in agricultural colonies, funded by Jewish organizations (e.g., the Jewish Colonization Association and the Jewish National Fund). The land was often bought from absentee landlords, especially in Beirut or Damascus, Major areas of purchases and settlement included: theCoastal Plain and Galilee - Early settlements like Petah Tikva (1878), Rishon LeZion (1882), and Zikhron Yaakov (1882); and the Jezreel Valley acquired largely through Baron Edmond de Rothschild's efforts. The indigenous Jewish communities - Hebron, Jerusalem, and Safed - (known as the "Old Yishuv") also benefited. Ottoman Nationality Law of 1869: Part of the broader Tanzimat reforms (1839–1876) to modernize the empire the law formally defined "Ottoman citizenship" (tabiiyet) and granted citizenship to all people born in Ottoman territory, regardless of religion or ethnicity—this included Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others across the empire. It applied to all residents of what is now Eretz Yisrael, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan—including both urban elites and rural populations. This law was especially important because it provided the legal framework for Taxation and Land ownership rights. World War I, Ottoman Collapse, British-French Mandates and the Republic of Turkey

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I led to the division of the Levant under the Sykes-Picot Agreement and League of Nations mandates. France took control of Syria and Lebanon, while Britain governed Eretz Yisrael and Transjordan under the British Mandate. Arab Muslims and Christians, who expected postwar independence, were instead subjected to foreign rule. Meanwhile, Armenian refugees—fleeing the 1915–1917 genocide—resettled in Syria and Lebanon, altering urban demographics in cities like Aleppo and Beirut. Treaty of Lausanne (1923): Signed in 1923, it officially ended hostilities between the Allied Powers and the Ottoman Empire and recognized the Republic of Turkey as its successor. It replaced the earlier Treaty of Sèvres, which had been rejected by Turkish nationalists lead by Ataturk. Under Lausanne, Turkey retained sovereignty over Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, while permanently ceding its claims to former Arab territories, including Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq. This treaty confirmed that the Ottoman Empire had no remaining claim to the Levant, which had already come under British and French control through the League of Nations mandate system. The treaty also abolished the system of foreign economic privileges known as capitulations and laid out terms for managing the former empire’s debt. Importantly, Turkey was not required to pay war reparations, a major diplomatic achievement for Atatürk’s new government. A major demographic shift followed, with a forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey—over one million Greeks were expelled from Turkey, and hundreds of thousands of Muslims from Greece resettled in Turkey. Lausanne marked the end of centuries of Ottoman sovereignty and ushered in a new era of Western-imposed governance, setting the stage for the national struggles that would follow across the Middle East. Jewish Immigration and Arab Resistance (1917–1939)While the Jewish Diaspora had been purchasing land in Eretz Yisrael The Balfour Declaration (1917) expressed British support for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Eretz Yisrael, prompting large waves of Zionist immigration, especially in the 1920s and 1930s. The Jewish population rose from 60,000 in 1918 to over 450,000 by 1939, driven by rising anti-Semitism in Europe. Tensions with the Arab population escalated into violence, including the Jaffa riots (1921), Hebron massacre (1929), and the Arab Revolt (1936–1939), which opposed both British rule and mass Jewish immigration. Rise of Arab Nationalism and Sectarian Fragmentation (1920s–1930s)Across the region, Arab nationalist movements grew in reaction to colonial control and demographic changes. In Syria, France divided the country into sectarian mini-states (Alawite, Druze, Greater Lebanon), deepening ethnic rifts and triggering revolts like the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927). In Lebanon, the creation of a Christian-majority Greater Lebanon by incorporating Muslim regions set up long-term sectarian tensions among Maronites, Sunnis, Shia, and Druze. In Transjordan, Britain installed Emir Abdullah in 1921, consolidating Hashemite rule over a largely tribal Arab population. World War II and the Road to Partition (1939–1947)The Holocaust created global sympathy for Jews and intensified demands for a Jewish state. Meanwhile, Britain, facing resistance from both Jews and Arabs, restricted Jewish immigration to Eretz Yisrael through the 1939 White Paper. Jewish militias grew stronger, and conflict with both the British and Arab population escalated. In 1947, the UN Partition Plan proposed dividing Eretz Yisrael into separate Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem as an international city. Jewish leaders accepted the plan; Arab leaders rejected it, triggering civil conflict. The 1948 War and Ethnic DisplacementWhen Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, neighboring Arab states invaded, beginning the Arab-Israeli War. Over 700,000 Arabs were expelled or fled from towns and villages in what became known as the Nakba (“catastrophe”), while Jewish communities in Arab countries faced violence and expulsion. Between 1948–1951, over 800,000 Jews fled from Arab lands, many resettling in the new State of Israel, where they were integrated into Israeli society. Summary of Ethnic Shifts (1918–1948)By 1948, the ethnic landscape of the Levant had been radically reshaped. Arabs in Eretz Yisrael, once the majority, became refugees throughout the region. Jews, having returned to their ancestral homeland, founded a sovereign state. Armenians rebuilt communities in exile, particularly in Syria and Lebanon. Kurds, Druze, and Alawites were drawn into the shifting political dynamics of post-Ottoman rule. These three decades marked a turning point, transforming the demographic order of the Levant and laying the foundation for modern geopolitical fault lines. SHORT HISTORY OF GAZA In the 1st century CE, Gaza was a thriving port city in the Roman province of Judea. It hosted a significant Jewish community, particularly in its surrounding areas. Jewish life in Gaza is referenced in the works of Josephus and Philo of Alexandria. Archaeological evidence confirms Jewish presence. With the rise of Christianity in the 4th century, under Byzantine rule, Gaza became a major center of early Christian thought and missionary activity. The most notable figure from this period was Saint Porphyrius, bishop of Gaza (395–420 CE), who led the destruction of pagan temples and promoted Christianity as the dominant faith. During his tenure, the Church of Saint Porphyrius was built, dedicated to the bishop after his death. It still stands today as Gaza’s oldest functioning church and one of the most important surviving structures from the Byzantine era. Most of the Jewish population were exiled. In 637 CE, Gaza was incorporated into the Rashidun Caliphate under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab. As Islamic rule spread across the region, Gaza transitioned into a Muslim city while retaining a Christian minority population. One of the most symbolic acts of this transition was the conversion of the main Byzantine church into the Great Omari Mosque, named after Caliph Umar. The conversion likely took place shortly after the Muslim conquest, in the mid-7th century, making the Great Omari Mosque one of the earliest Islamic religious institutions in Gaza. Over the centuries, it was expanded and rebuilt—most notably during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods—and it served as Gaza’s central mosque for Friday prayers and Islamic governance. Another key Islamic religious site is the Al-Sayed Hashem Mosque, believed to contain the tomb of Hashem ibn Abd Manaf, the great-grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad. This mosque became a site of pilgrimage and local spiritual importance, further solidifying Gaza’s religious identity in the Islamic era. During the last century of Ottoman rule (roughly 1800–1917), Gaza underwent a period of gradual transformation from a modest provincial town to a more integrated part of the empire’s administrative and commercial framework. Though still relatively small in population and economic scale compared to major Ottoman cities, Gaza benefited from Tanzimat reforms (1839–1876), which aimed to modernize governance, improve infrastructure, and increase central control. Ottoman authorities built new roads, improved trade routes, and expanded telegraph and postal services, connecting Gaza more closely with Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Egypt. The city remained predominantly Sunni Muslim, with small Christian and Jewish minorities, and was surrounded by tribal and Bedouin communities with whom it maintained complex relationships involving land, trade, and conflict. Gaza’s economy continued to revolve around agriculture—especially olives, grain, and soap production. CONTEMPORARY TURKEY RECOGNIZES OTTOMAN CITIZENSHIPTurkey has granted certain Gazans of Ottoman descent Turkish citizenship or special residency status. Some propose that Turkey instituted a law similar to Israel’s Law of Return, which would allow descendants of Ottoman Gazans a special Turkish citizenship and enable their repatriation to Turkey or Turkish-administered areas in Syria.

|

Updated to November 29, 2025 v2